How I landed in Product

The barriers I had to break through. Some mental, some societal. All bullsh*t.

It’s true what they say. Product isn’t for everyone. I definitely didn’t think it was for me. But I also didn’t think working was for me, either. More on that in a moment.

I didn’t title this “How to land a job in Product” because it’s different for everyone and every context. My hope is that by sharing my story, anyone can gain some insight for their unique situation, even if you don’t work in product. More than happy to connect with you and talk specifics. But I always hesitate to document it like there is some magic formula (there’s not) and I have it figured out (I don’t).

My coaching clients and mentees generally fall into one of four categories. Maybe you feel “stuck” in one of these transitions yourself.

Not in tech > want into tech

In tech, not in product > want into product

In tech and product > want into product management

In or not in tech and/or product or product management > want to get promoted (this is just the bucket for all the people everywhere who want to grow their career)

I had three initial barriers to overcome:

Women don’t work

Women don’t want more

Women don’t work in product

Here’s how I landed in Product and why I love what I do.

It begins with how I went from struggling stay-at-home mom to career dabbler.

Breaking barrier #1: Women don’t work

I was born and raised in a strict religion in the strictest of decades. As Nate Bargatze said recently in his standup comedy special:

I had 80s and 90s Christian parents. Well, that's the most Christian you can ever get of the Christian. I think Jesus had more fun than I did.

Side note: He’s in Salt Lake this weekend and I have tickets to see him live. Excited to have laughing-so-hard-I-cry to look forward to right now.

As a pious young woman in the church, you were not supposed to want to work outside the home. While the boys were earning merit badges like nuclear energy or personal financial management and attending career nights, the girls were learning how to be dutiful wives and mothers and kneeling for modesty checks (if your skirt didn’t touch the carpet, you were going to hell).

Any examples of working women were based on tragic stories of a beloved husband’s death, or, heaven forbid, divorce and singledom. I still remember “Sister B,” the most elegant and wordly woman I could imagine at the time. She and her husband had a huge, beautiful home filled with real wood beams. She worked outside of it. It felt daring, confusing, unreachable.

I started working out of necessity. Not monetary necessity. In fact, when I was trying to decide whether I would role reverse with my husband a year after our first son was born, I had this exchange with my therapist:

“But I’ll never be able to make as much as my husband does. He makes $16 an hour!”

“Bullshit.”

He replied as if it was the most “duh” thing ever uttered in the history of ever.

It was the last thing I expected him to say. First, I thought we were both on board with my whole “woe is me” narrative up to that point and second, he was a prominent leader in the aforementioned religion. There was no cursing.

But he cursed.

He must really mean it, then, I thought.

The necessity for working was actually based on a year of undiagnosed and untreated postpartum depression. The darkest and loneliest moments had me planning how to end it all. Suicide is a leading cause of maternal mortality and, in short, I was in very real danger of becoming one of the 20%.1

My first job was as an after-school English tutor at a Sylvan Learning Center-type company for six hours a week. I belted out Celine Dion’s new One Heart album on my 90-minute roundtrip commute for my 120-minute shift and felt one part free and one part failure.

Breaking barrier #2: Women don’t want more

My boys heard, “You get what you get and you don’t throw a fit” from their teachers on the regular. My generation’s version of this was, “You’re gettin’ too big for your britches” and “You’re cruisin’ for a bruisin’.”

You never wanted more. And you definitely never asked for more. Especially as a girl.

After my very part-time gig ended, I beat out 50 applicants for one of two spots in a full-time, paid summer internship at a local tech startup. In 2003, paid internships were rare. So earning $9.50/hr was thrilling at first. By the end of the summer, though, I wanted more. The other intern and I hatched a plan, wrote a long proposal, and marched in unannounced to the CEO’s office. We recommended (um, demanded?) that we both be kept on full-time and our pay be raised to $15/hr each. I was fired the next day.

That internship was where I became friends with Anne-Marie Wright, our CMO, who was friends with the founders who were hiring at another tech startup. I joined those co-founders as their sole technical writer and 17th employee. I cannot overstate how incredibly formative those two years were for me. My memories from that time are probably some of the most vivid of my entire two-decade career thus far.

I reported into Head of Product, essentially the Chief Product Officer. Here are the three lessons I learned during my first real stint working full-time and in a product organization.

Lesson #1: Be useful. Say “yes.”

At a startup, there is always a lot to do. And then more to do. And then more. It never ends. You never end the week feeling content. And I didn’t have ANYthing figured out yet related to work-life balance or my life rhythm. None of it. My workaholism was taken full advantage of. I worked late nights most weeks, I worked weekends, and I said “yes” to everything. Which meant I got to experience a lot of different things.

I learned xml for single-sourced technical documentation; I ran the project with the head of marketing to completely revamp our website; I built an internal website using HTML for our field reps to request documentation and software (this was back when we still burned the code onto CDs — google it); I wrote patent applications; I gave product trainings; I created status presentations for the big head hancho Department of Defense customers.

I remember sitting in church on Sunday and getting an urgent text to come into the office. I needed to rewrite our technical procedures in a way that would allow our software to be installed in <1 minute. It was a life or death situation. I had never felt more alive.

My favorite was one year in, my boss came to me and said, “I need to hire a Technical Writing manager for building out a team of more yous. Can you write the job description for that role?” It took me about an hour. I printed it out (google it) and handed it to him. He looked it over, handed it back to me and smiled, “You’re hired.”

Coolest way to get promoted, ever.

Lesson #2: Be in the room.

We had a special room at that company. A SCIF. Or a “sensitive compartmented information facility (/skɪf/), in United States military, national security/national defense and intelligence parlance, is an enclosed area within a building that is used to process sensitive compartmented information (SCI) types of classified information.”2

In the SCIF were sensitive documents, yes, and for those of us who had the right level of clearance, we could also enter the room and see newspaper clippings scattered on the table. Their significance was understood, never discussed. (This was 2004 btw. George Bush in the White House. Post-9/11. Google it.)

Being in that room was thrilling but I loved being in the big board room where we discussed product strategy and roadmaps even more. Because my team was over all the technical documentation and delivery of our software, I needed to understand what was coming and why. I (mostly) silently soaked in all the context like a toddler with their million whys.

Lesson #3: Be ready to walk.

While the consistent salary and responsibility increases fed my desire for more, the lack of an HR department was the reason I left after only two years. (Our CFO was the HR department.) The “more” I wanted and could never have was to feel safe in my workplace. It was clear nothing was going to change. So I quit. On my way out the door, my boss made a clumsy attempt at a peace offering by gifting me a book. The inscription was addressed to someone else. I threw it away.

My stocks had vested, though. Holding my first payout check a few years later definitely gave me a taste of startups I’ve craved for the rest of my career.

From that 200-person startup, I bounced around to four jobs in <9 months. The highlights from that period were:

Got my Mortgage Loan Officer license.

Almost burnt down the building of my mortgage company. The firemen were not amused, but they were kind. Don’t put a pizza in the toaster oven and then leave the building with no way to get back in.

Left because of how icky it felt offering high-priced mortgages to people with <450 credit scores. This was 2006; if you don’t know what happens next, may I recommend The Big Short?

Incorporated a startup of my own, blew through a lot of cash, and didn’t bring on one client.

Questioned whether I was really cut out to be the sole breadwinner. My husband looked into going back to school and starting a new career.

Became pregnant with my second baby.

Took an Instructional Designer contract job at American Express for $32/hr, the best part of which was being paid to eat lunch.

It was in the cream-colored, dimly lit cafeteria that I started and finished the book that would change my career trajectory forever: Barbara Stanny’s (now Huson’s) The Secrets of Six-Figure Women.3

I quit the next morning. Then came home and told my husband.

“I’m going to be a six-figure woman!” I announced to my husband. If he was skeptical (or scared out of his mind), he never showed it.

I was our only source of income. We had a four-year-old who had just been diagnosed as autistic (he wasn’t; we learned a few years later he had been deaf since birth), a mortgage, car payments, and a large, fluffy dog who had just chewed up Season 9 of our Friends DVDs. (We re-homed him soon after.)

I needed a full-time job at almost double the salary I ended my last full-time job at OR a contract job that paid at least $48/hr.

At a local publishing company, the final onsite interview question from a member of the three-person panel was, “What are your salary requirements?”

“$105,000 base,” I said with no hesitation.

Smirks and knowing smiles. I was not deterred.

Phone screen after phone screen, the recruiters said, “That’s out of range.” I even had one guy emphatically advise, “You don’t have enough experience. You’ll never get that much!”

My gumption in full gear, within three weeks, I got it. I was hired as a contractor at just under $48/hr at Wells Fargo. As my nephew says, “Boom, done.”

Once I was in the door, I realized I had joined another startup. (A startup with a big backer, obviously.) I was in the unprofitable Health Benefit Services division, service provider of the new HSA cards. There were <200 people, just like my first company. We were clearly our own little island of misfits ranging from fresh-out-of-college know-it-alls like me and seasoned, politically paranoid banking executives. The rally cry from our product line CEO, Jose Becquer, was always “Profitability!” and then he would share another one of his favorite motivational quotes.

I remember being in the buffet line next to him at an offsite. He had lost a substantial amount of weight. I have made it a rule never to comment on someone’s weight loss directly. So I grabbed a few more carrots and said something like, “You seem strong and healthy lately, Jose!” He thanked me. A few minutes later when he addressed the room of hundreds, he started out by joking, “Many of you have noticed my weight change. Don’t worry, I’m not sick or anything.” A few months later, he was gone. He died from cancer at age 50.

I stayed in banking for 10 years, until 2016. Each time in small, innovative departments that operated more like startups than financial services behemoths.

I had also broken the “women don’t want more” barrier and was able to do the following:

Because I didn’t know any better, as a Sr. Technical Writer short-term contractor, I filled in the many gaps I saw related to getting stuff done. So they hired me as a full-time Project Manager within three months. (The original title / comp range they offered me was “Project Specialist” but I wanted, asked for, and got more.)

Because my title was officially Project Manager, I was automatically absorbed into the new PMO formed during a major re-org (PMO = Project or Program Management Office).

Because I didn’t know any better, I got in way over my head managing massive projects and programs with little formal training and a bull-in-a-china-shop approach. Needless to say, I was still learning how to play nice in the sandbox.

Eventually I got my PMP and joined an actual, mature ePMO at the next company (PMP = Project Management Professional certification from the Project Management Institute; there is no equivalent in the Product world).

Once we had over 40 Project Managers, it was time for some hierarchy. I was promoted from Project Manager to Program Manager (PgM), reporting to a Portfolio Manager.

When the newly formed PgM roles were announced, I was not one of them. A week later, after one of the eight originals left the company, I was told behind closed doors, “We always knew he was leaving and we always wanted you to be one of the Program Managers.” It was one of those frustrating I’ll never understand corporate politics moments.

Breaking barrier #3: Women don’t work in product

I’ve read different stats about gender parity in product management. Some say it’s 50/50 and some say 35% women, 65% men. Regardless, getting into product management became harder for women around this time, based on a small gender-biased change.

But something changed during the mid-2000s, when Google emerged as a strong training ground for Product Managers. A former Google PM shared how, around 2004, the company changed its requirements for PMs. “Google had a series of meetings with current and former engineers to understand what they thought could be improved,” they explained. “One of the big pieces of feedback was PMs were 'not technical enough' or 'too businessy'. The solution they came up with was to filter down to technical PMs, [with] the requirement that they have a degree in computer science — or in a related field like electrical engineering.”

In 2005, women only earned about one in five CS degrees in the US, and that trend continues to this day. I believe that the new technical requirement changed the pool of potential PMs to one which was heavily male dominated and thus unintentionally led to the industry moving away from gender balanced teams.

On top of this, churn in tech is much higher for women. According to a 2008 Harvard Business School study, 41 percent of women leave a decade after starting in tech, compared to 17 percent of men. If women don’t get a strong start in Product, and leave tech at higher rates, how will we get back to a gender parity again?4

Over 90% of the product managers and leaders I worked with during the first decade of my career were men. (I actually think it was 100% but it’s been so long, it’s possible there were a few women.)

In 2013, about a decade after Google started requiring Product Managers to have Computer Science degrees, I was a newly promoted Program Manager and embedded with the EVP of one of the bank’s product lines.

He requested me because I had done previous project management work with them. For the two years prior, I worked closely with the bankcard VP and his team and the mobile banking VP and his PMs and BAs. Because I didn’t know any better, this is when I actually started doing product management.

Here’s what being a Product Manager with a Project Manager title looked like:

Instead of just keeping a WBS (Work Breakdown Structure or project plan) in order and hounding people to get their tasks done, I worked hard to fully understand the business strategy and goals. I was always hungry for more context. I asked a lot of questions. I traveled to their offices and sat with the men and listened to them talk about the market, the competition, the numbers and strategize.

Eventually, I understood the context so well I could consult and offer ideas and suggestions in these meetings. I helped them connect the dots between their strategy and the execution. I elevated myself from notetaker to more of a co-equal product-like person.

I read and made suggestions in the PRDs (Product Requirements Documents).

I helped the Business Analysts take the PRDs and write the business and technical requirements in detail.

I read and edited the patent applications.

I led large and long product discovery work sessions. I rallied everyone around the vision and strategy of the initiative. I helped the teams assess multiple solutions.

I loved partnering with the Solutions Architect to whiteboard the backend infrastructure needed to fulfill all the requirements. I made sure he was involved very early on.

I sat side-by-side with the Engineers multiple times a week and answered their questions. I made design choices and product decisions in the moment so we could move faster. I didn’t have to constantly bother the VP and team because I felt confident speaking on their behalf. I knew when a decision needed their input and when it didn’t.

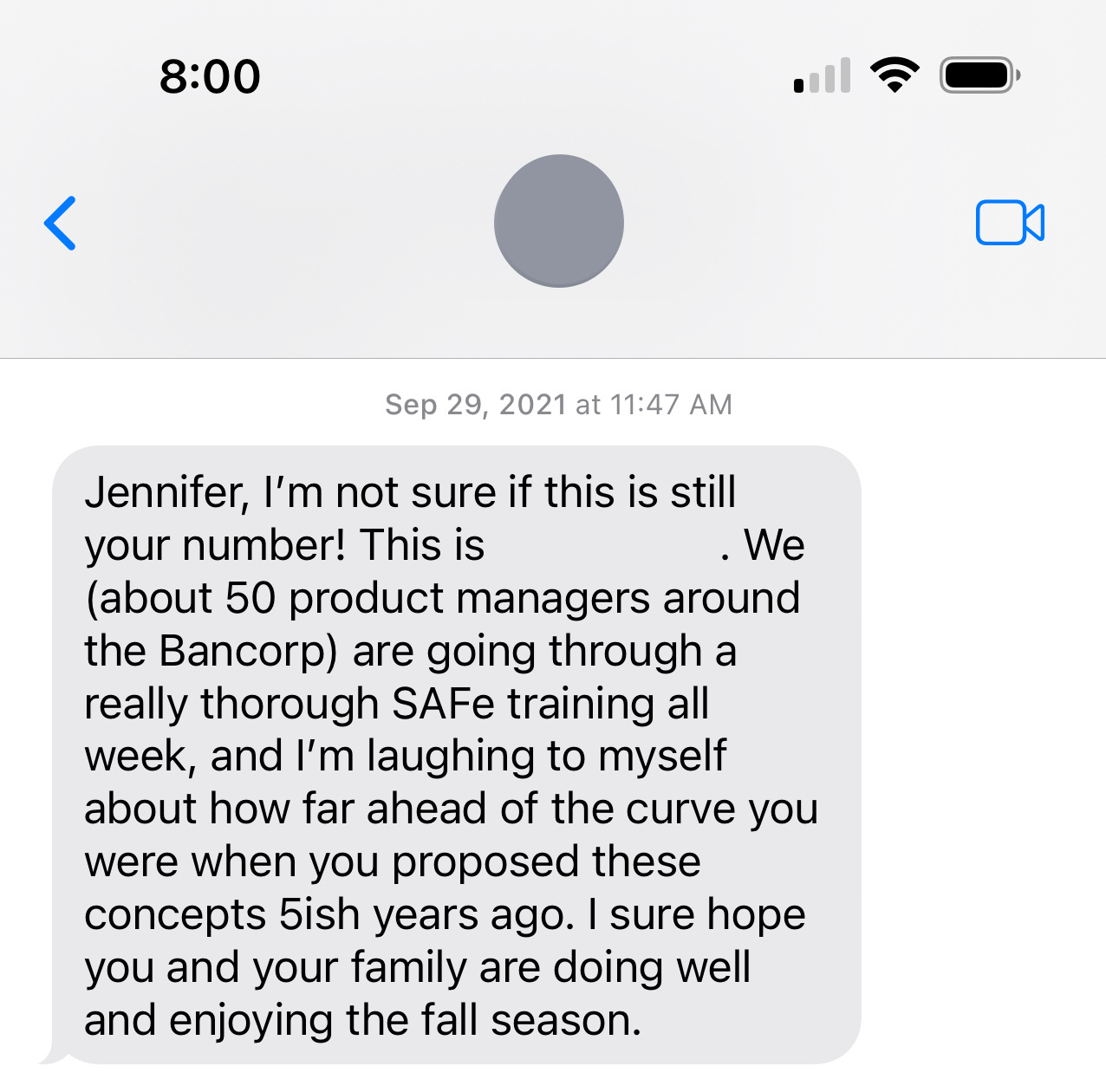

I learned Agile methodologies through certifications and trainings and worked to implement best practices in my development teams. Some were more receptive than others. It was banking, after all: The land of waterfall. They’ve made strides since I was there. In fact, I received this delightful text a few years ago.

Because I was part of the central Technology group of about 1,700 people serving the central product lines who served the regional banks, my customers were all internal. For all of the people I interacted with, the majority were not in my building. I had to get in my car and drive to several different locations in the area every week. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was following the NIHITO principle (Nothing Interesting Happens in the Office). I.e., get out of the building and talk to and observe customers in their natural habitat.

It was also during this period that I realized if I wanted to grow my career and salary significantly, I couldn’t do it in a PMO. My next step from Program Manager would be Portfolio Manager. An aggregator of the aggregators. No, thank you.

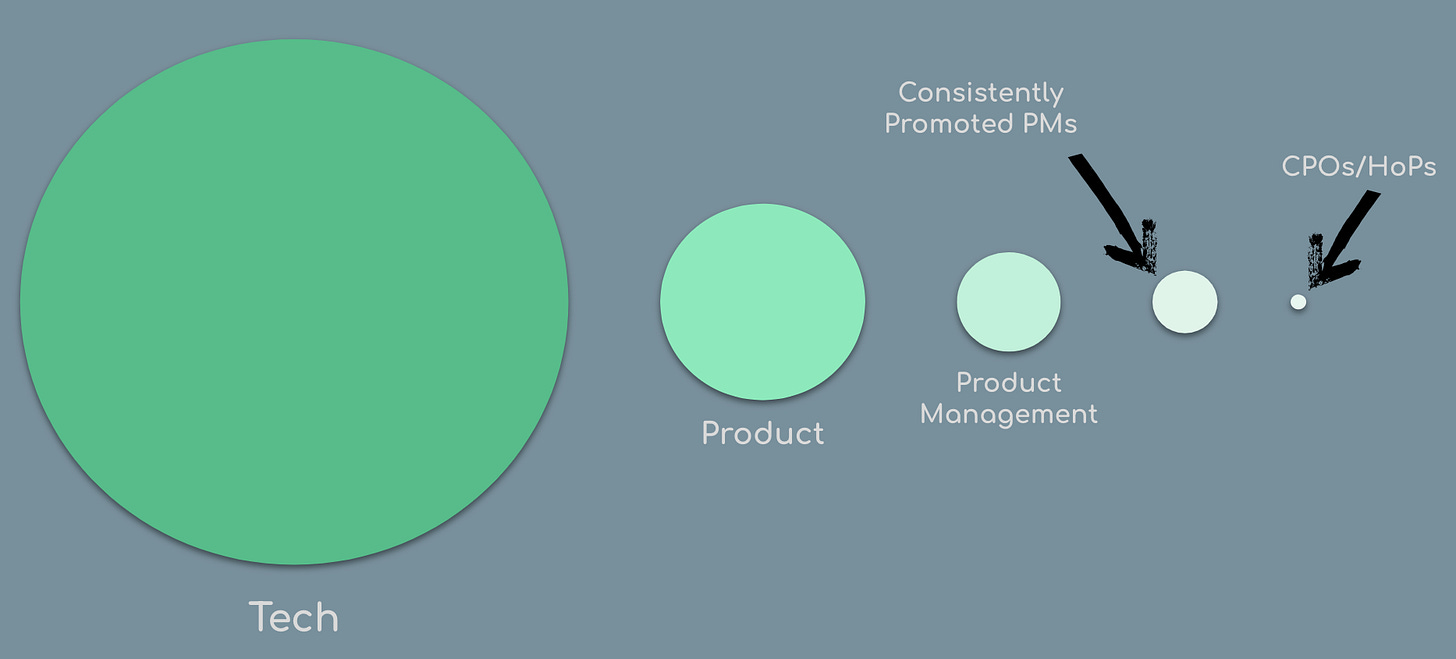

I knew I was too far removed from the customer and the revenue, from making a bigger impact and therefore a bigger paycheck (I was still making <$115,000 base). I didn’t want to go into Sales (too risky) and I didn’t want to do Customer Service (too exhausting). I saw my options like this:

When there was an opening for a Sr. Product Manager in the product line I had been serving, I applied. I thought for sure I had bombed the final panel interview. My new boss didn’t even bother to show up. That night, I sat with my two boys in my car, bawling. We were on our way to see Maleficent at the theater and I couldn’t pull out of the McDonald’s parking lot and drive safely. My wise 12-year-old listened and then put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Mom, they all know how this feels. They have done bad at interviews before too. If they are more successful now, you will be successful too. They aren’t thinking anything bad about you. It’s going to be okay.”

I got the job. And the reason my new boss skipped the interview, I found out later, is because he had made up his mind to hire me before I even applied.

I got a slow start as a new Product Manager. I would sit in my office and not really know where to begin. And I recall being in meetings and my products were never discussed. I asked (likely complained) about this to my VP boss. He simply said, “Who do you think advocates for your product lines?” It was rhetorical.

Clearly, I had a lot to learn.

Over time, I realized that the steel-fisted negotiator that came out of my EVP when we negotiated my salary bump was also something that would apply to negotiating with vendors for products I was launching. It was like a drug to him. We were in negotiations with the core third-party vendor for over a year. As someone who values GSD above all, it was crazy-making. I knew I had to get out.

When I told the EVP I was leaving, he said, “I was really hoping you would stay long enough to launch the new product.” Unsurprisingly, 18 months later at the grocery store, I ran into the Project Manager and she shared, “We still aren’t fully launched yet.” I grabbed my almond milk yogurt and ran, grateful I got the hell out of there.

Yes, I wanted to leave for the above reasons and more but mostly what I realized is that traditional banking is not the future. It really hit me when I learned that the average age of our customer was 69. With half our customers only expected to live another decade, this was an industry ripe for disruption. In fact, I had already been partnering with a fintech company and saw clearly how these companies were the future. My future was SaaS and agile and a larger, more diverse product management team I could learn from.

Next up: How I landed in Product, continued

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8976222/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sensitive_compartmented_information_facility

https://www.barbara-huson.com/

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-happened-women-product-deborah-liu/